Need to hire an engineering firm quickly for Defense R&D work?

Looking to cut down on paperwork and waiting time?

You need our guide breaking down six federal contracting methods from fastest (1-2 days) to most complex (multi-month).

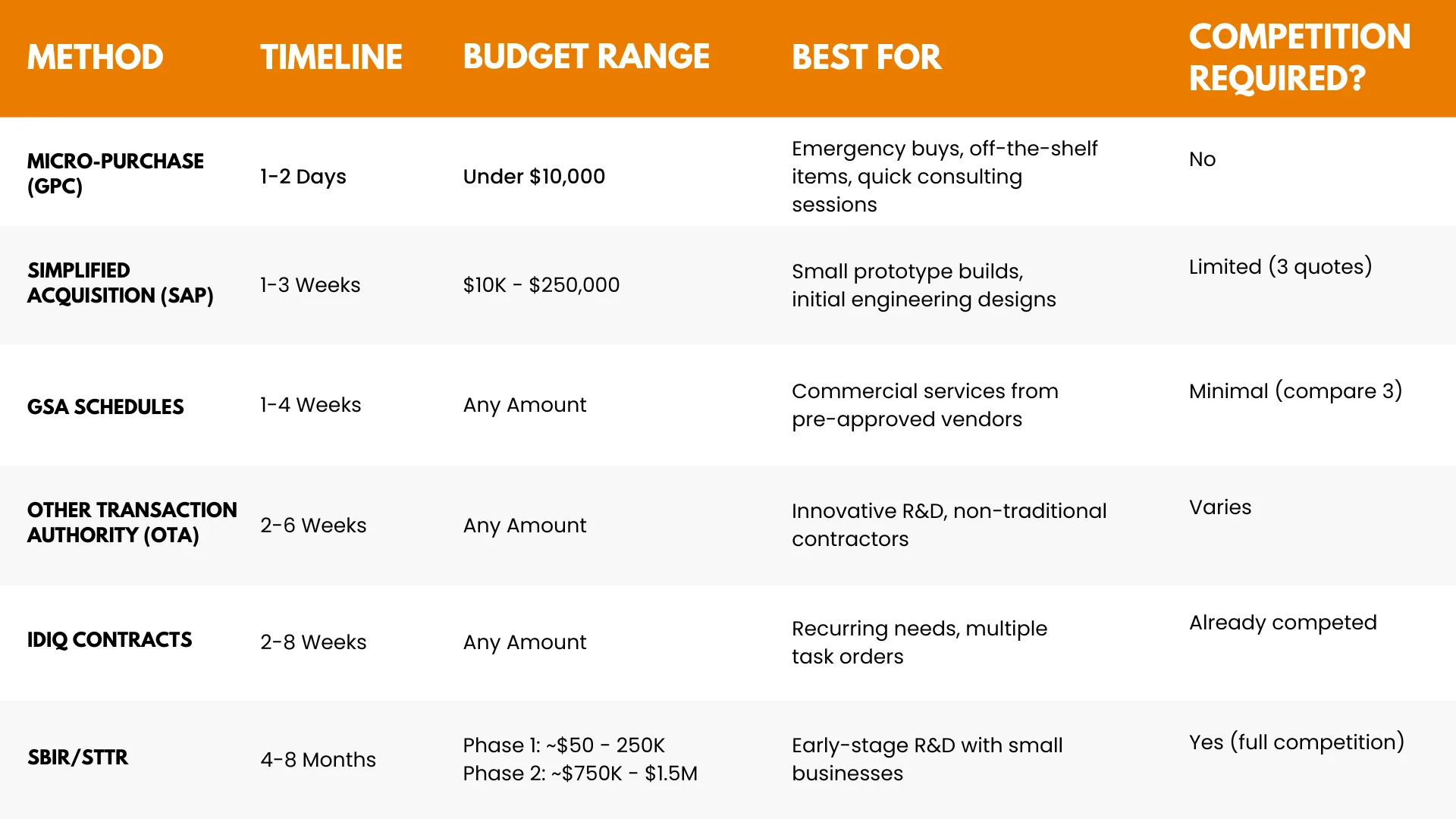

In a rush? Check out our quick reference table to help you choose the right option for your project timeline and budget!

Quick Reference: Federal Contracting Methods Guide

Decision Making Questions:

- Need it this week? Micro-Purchase or existing IDIQ

- Under $250K and need it this month? SAP

- Working with a small innovative company? OTA or SBIR/STTR

- Need multiple deliveries over time? IDIQ

- Vendor already on GSA? GSA Schedules

Get to Know Your Contracting Officer

Throughout this process, maintain a collaborative, friendly relationship with your contracting officer. They are your ally in navigating the rules quickly. It’s okay if you’re not familiar with the procedures – you can rely on their expertise. Just be clear about what you need and when you need it. If something seems stuck, ask if there’s anything you can do or if another method might be faster. Keep in mind that for very urgent needs, there are often exceptions or expedited processes the CO can invoke (like emergency purchase authority), but those are situational. These options are generally accessible and legal for everyday quick-turn projects, especially in the prototyping realm.

Getting Started Quickly: Your 5-Step Action Plan

1. Define Your Needs (Budget and Timeline)

Simplify everything down to one sentence: “I need [a specific service] for approximately [$ amount] by [date].” That’s it. Don’t worry about the jargon.

2. Call Your Contracting Officer NOW

Tell them: “I have a $50K rapid prototyping requirement. What’s our fastest contracting method?” They’ll immediately know whether you need to use SAP, an existing IDIQ, or micro-purchase.

3. Prepare Your Justification (If Needed)

- Justifying a Sole Source vendor? Write a few sentences to explain how just this vendor can meet all your needs.

- Using SAP? List 2-3 small businesses you could contact.

- Under $10K? No justification needed!

4. Get Your Quote!

- Micro-purchase: Email vendor for price

- SAP/GSA: CO will handle quotes (takes 2-5 days)

- OTA: Vendor will provide a brief technical proposal

5. Execute

Once approved, send the vendor:

- Who to invoice (your finance POC)

- Where to deliver/who to work with (your technical POC)

- Any reporting requirements

Pro Tip: Ask your CO upfront: “Do we have any existing contract vehicles I can use?” Half the time, an IDIQ or BPA already exists that can save you weeks of leg work.

Micro-Purchases (Government Purchase Cards)

What It Is

A Government Purchase Card (GPC) is essentially a government-issued credit card used by authorized personnel to buy goods or services directly. Micro-purchase procedures refer to very small purchases below a certain dollar threshold. Currently, the micro-purchase threshold (MPT) for most purchases is $10,000[xii]. (It can be slightly higher in certain emergency or contingency situations, but for normal use it’s $10k.) Purchases at or below this threshold do not require competitive quotes or extensive paperwork – they’re like swiping a credit card for an office expense. A lab’s administrative or contracting staff often have GPCs for this purpose.

When to Use It

Use micro-purchase/GPC for very small or urgent needs, especially if you can easily define the item or service and it costs $10,000 or less. For example, if you quickly need a custom circuit board design from a small company estimated at $8,000, this could be done via GPC. The process is simple: identify the item/service and vendor, ensure the price is within the micro-purchase limit, then have your unit’s purchase card holder simply buy it directly (often by phone or online payment). The card holder will verify the price is fair (maybe by comparing to an online price or catalog). No formal competition or contract is required by law[xv]. This is the closest to an “easy button” in federal purchasing. Just be sure to clearly communicate what you need to the card holder and provide any paperwork they might need (like an invoice or quote from the vendor). In summary, if your prototyping support need is small-scale, the GPC route can meet it within a day or two, making it the fastest option.

Pros:

- Fastest Method: Micro-purchases are extremely fast and simple. If your need is small, the authorized person can literally just pay with the government credit card. There’s no formal contract needed and no waiting for bids[xiii][xiv].

- No Competition Required: For micro-purchases, the law says you don’t have to solicit multiple quotes as long as the price is reasonable. This means you can directly choose a vendor and buy, which is effectively a built-in sole-source allowance for small buys.

- Minimal Paperwork: Documentation is minimal – typically just the credit card log and maybe a note of what was bought. This keeps the overhead near zero and the purchase almost as easy as an online shopping order.

- Immediate Needs Met: This method is great for grabbing off-the-shelf items or quick services. If a prototype effort needs a few parts, tools, or a short consulting session under $10k, a GPC purchase can handle it in a day. It’s essentially the “instant purchase” method in the federal toolkit.

Cons:

- Dollar Limit: The obvious drawback is the strict dollar cap. Anything over the micro-purchase threshold requires a different method. You can’t split a larger requirement into many $9,000 chunks just to use the credit card – that’s not allowed. So this is only for very small procurements.

- Card Holder Availability: You need an authorized card holder in your organization willing and able to make the buy. In a lab, this might be a resource manager or contracting specialist. If you’re not sure who that is, you have to find them, which could introduce a delay.

- Scope: Generally used for simpler purchases (buying supplies, paying for a short service). If your need is complex (like a detailed engineering project), even if it’s under $10k, the card might not be ideal because you may still want a written work agreement. The GPC is best for straightforward buys (e.g. purchasing a piece of equipment or a few hours of consulting).

Simplified Acquisition Procedures (SAP for Small Purchases)

What It Is

Simplified Acquisition Procedures (SAP) are streamlined buying methods for contracts under a certain dollar limit (the Simplified Acquisition Threshold). Currently this threshold is around $250,000 for most purchases[vii]. SAP is basically a “lightweight” version of contracting: the rules are simpler, the paperwork is less, and it’s often quicker. The purpose of SAP is to reduce administrative costs and burden, promote efficiency, and give small businesses a fair shot at government work[viii]. In practice, this means if your needed prototype engineering work is relatively low-cost, the contracting officer can use simplified procedures instead of a full formal contract competition.

When to Use It

Use SAP when your required prototyping services are under the dollar threshold and you need a reasonably quick procurement. For example, if you need an engineering design or a small prototype build that costs, say, $100,000, SAP is a great route. To proceed, you would tell your contracting officer, “This request is under the simplified threshold, can we use Simplified Acquisition Procedures?” Provide a brief description of what you need (a simple Statement of Work or purchase description). The contracting officer might solicit a few quick quotes from potential vendors (often informally by email/phone or via an online small business marketplace). If you already have a preferred small business in mind (and for good reason), you can work with the CO on a sole-source justification – basically a memo explaining why no other supplier can do this job as well or as fast. Once the contracting officer determines the price is fair and documents the decision, they can issue a purchase order or small contract to the vendor. This could be done in a matter of days to a couple of weeks, generally much faster than a large contract. SAP is a practical choice for early-stage prototypes when funds are limited and speed matters.

Pros:

- Lower Admin Overhead: SAP contracts require less paperwork and approval steps than large contracts. This saves time for everyone[ix].

- Faster Awards: Because the process is simpler (often just getting a few quotes or an informal proposal), awards can be made much more quickly than through the full bidding process.

- Small Business Friendly: By law, simplified acquisitions typically prioritize small businesses for awards[x]. This is good if you want to hire a small engineering firm – the rules encourage giving them the opportunity.

- Flexibility in Competition: Under SAP, contracting officers often just need to seek a few quotes (commonly 3) or use discretion to ensure a fair price[xi]. There’s no lengthy formal RFP If only one source is truly available (sole source), it’s easier to justify at these dollar values than for large contracts.

Cons:

- Dollar Limits: You can only use SAP up to the simplified threshold (∼$250K, or higher in some special cases). If your project needs more funding, you might have to break it into smaller chunks or use another method (breaking into chunks solely to use SAP is generally not allowed, though).

- Still Some Process: While simpler than big contracts, SAP isn’t instantaneous. The contracting officer must do basic market research, ensure price reasonableness, and document the purchase. This could mean reaching out to a few vendors for quotes or using an existing streamlined platform. It’s faster than formal contracting but not as fast as a micro-purchase.

- Competition Still Preferred: Simplified procedures encourage competition at a small scale. If you want a specific vendor without seeking others, you’ll need a sole-source justification (a short explanation of why that vendor is uniquely qualified or time is critical). It’s doable but must be written and approved, which is an extra step.

GSA Schedules (General Services Administration)

What It Is

GSA Schedules (now often called GSA Multiple Award Schedules) are basically a catalog of pre-negotiated contracts that federal agencies can use to buy products and services. If a company (like an engineering firm) is “on the GSA Schedule,” it means they have an active contract with GSA listing their services/prices, and any government agency can place an order directly through that contract. Using a GSA Schedule is faster than starting a new contract from scratch because the vendor is already pre-vetted and terms are set. Think of it like Amazon for federal procurement – you still have to choose an item/vendor, but the marketplace is pre-approved.

When to Use It

Use GSA Schedules when you know of a suitable small business or contractor that is on the GSA list and your requirement fits a commercial service category. For example, say you need an engineering design service to build a prototype device and there are contractors on GSA Schedule under “Engineering Services” who do this – then your contracting officer can simply request a quote from that firm (or a few similar firms) and issue a task order or purchase order against the GSA contract. The steps for you: identify if your desired vendor is on GSA Schedule (you can search on GSA’s eLibrary or ask the vendor). If yes, tell your contracting officer, who can then quickly execute the order. If multiple vendors are available, you might quickly review a couple of quotes for price reasonableness. Overall, GSA Schedule orders can be turned around relatively fast (days to a couple of weeks, typically) because most of the heavy lifting (competitive award and pricing) has been done upfront by GSA. Use this option if speed is important but your need is a bit larger than micro-purchase and the vendor pool is known and on contract.

Pros:

- Streamlined Purchasing: Because the pricing and T&Cs are pre-negotiated, a lot of the work is already done. Agencies can order quickly and efficiently from GSA Schedule holders[xix]. This can save weeks of contracting time.

- Reduced Competition Requirements: When using GSA, you don’t have to do an open public solicitation. Typically, you just need to compare a few schedule vendors or solicit quotes from a few on the schedule (often 3 is enough) and then pick the best value. This is a smaller, faster competition within a ready pool, as opposed to a full open bid. If the dollar amount is below the simplified threshold, the process is even easier.

- Sole Source Possible (with Justification): If you have a particular vendor on GSA you want, it’s sometimes easier to justify a limited-source buy on the schedule than in the open market. The contracting officer can write a brief justification if only one schedule source can meet the need or if it’s urgent, then buy directly from that vendor’s GSA contract. The schedule mechanism supports this kind of flexibility.

Cons:

- Vendor Must Be On Schedule: This method only works if the company you want to hire already has a GSA Schedule contract for the type of service you need. Not all specialized engineering firms (especially very new or niche ones) will have a schedule listing. If your preferred vendor isn’t on GSA, this path is closed unless they join (which is not quick).

- Not Always the Absolute Fastest: While quicker than open bidding, using GSA still involves some process. The contracting officer might post a request for quotes on GSA’s eBuy system or reach out to multiple vendors on schedule. This can take days or a couple of weeks. It’s efficient, but something like a micro-purchase or existing OTA could be faster for small needs.

- Scope Limitations: GSA Schedules cover a lot, but they are focused on commercial products and services. If your prototype work is very R&D-heavy or not a clearly commercial service, it might not fit well under a GSA contract category. Also, large dollar orders might require more justification or additional approvals even on schedule.

Other Transaction Authority

What It Is

Other Transaction Authority (OTA) is a special procurement method used mainly by DoD and certain agencies for research and prototyping projects. An OTA agreement is not a normal FAR-based contract – it’s an alternative agreement that bypasses many of the usual federal contracting rules, making the process faster and more flexible[i]. OTAs were designed to attract innovative companies (including small businesses and non-traditional defense contractors) that might avoid the federal market due to heavy regulations. OTAs are commonly used through consortia or programs like Defense Innovation Unit’s Commercial Solutions Opening.

When to Use It

Use an OTA when you need a rapid prototype developed and want to involve an innovative small business or tech company without the full FAR contract process. Talk to your contracting officer about whether your organization has OTA authority or can tap into an existing OTA consortium. The process usually involves a short proposal or Statement of Work from the company and a quick negotiation of terms. In plain terms, you’d describe what you want built, and the contracting office uses the OTA mechanism to make an agreement with the vendor. This can happen much faster than a normal contract. If you have a specific company in mind (sole source), an OTA can potentially be awarded directly if justification exists (e.g. unique capability), or through a streamlined competition among a small pool of innovators. Overall, OTAs are ideal for early-stage prototypes where speed and flexibility are critical.

Pros:

- Speed and Flexibility: Fewer bureaucratic requirements than standard contracts, so deals can be made faster and tailored to the project’s needs[ii]. For example, you can negotiate terms (payment milestones, data rights, etc.) more freely.

- Attracting Innovation: Allows working with non-traditional vendors (startups, small tech firms) who might not have government contracts otherwise. The lighter process encourages innovative solutions.

- Follow-On Benefits: If the prototype succeeds, the government can move to a follow-on production contract without a new competition (sole-source follow-on) under certain conditions[iii][iv]. This means you won’t have to bid out the project again to scale it up – a big plus for continuity.

Cons:

- Limited Scope: OTAs can only be used for specific purposes (like R&D and prototyping directly relevant to DoD needs). They’re not for every purchase.

- Not Always Understood Locally: Your local contracting office might have limited experience with OTAs, which could slow things down if they need approvals or guidance.

- Conditions Apply: To use an OTA for prototyping, typically at least one non-traditional defense contractor or small business must be involved, or the vendor must cost-share some of the project, unless an exception is made[v][vi]. These rules ensure OTAs aren’t used for just any routine contract.

Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) Contracts

What It Is

An Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract is a pre-arranged contracting vehicle that an agency sets up with one or multiple vendors for a broad scope of work. “Indefinite delivery” means the exact timing and delivery of orders are not fixed in advance, and “indefinite quantity” means the exact amount of work isn’t set – instead, it guarantees a minimum and allows up to a maximum. Essentially, an IDIQ is like an “umbrella” contract under which the government can issue task orders on the fly when needs arise. Many agencies create IDIQs (sometimes called “task order contracts”) for recurring needs like IT services, engineering support, etc. Once the IDIQ is in place, buying specific services is much faster because you’re just placing an order, not negotiating a brand new contract each time[xx] [xxi].

When to Use It

Use an IDIQ if your organization already has one you can use, or if you plan to do multiple projects over time and can invest in setting one up. For instance, if your department has a “Rapid Prototyping IDIQ” with a contractor, and your project falls under its scope, you can simply define your task (what needs to be built/tested) and have the contracting officer issue a task order for that work. This could be done in a matter of days or weeks, with minimal new paperwork, since the vendor is pre-qualified. If no such contract exists, and you find yourself repeatedly needing outside help for prototypes, you might propose establishing an IDIQ contract for your lab (this is a longer-term solution). The bottom line: An IDIQ is fantastic for quick-turnaround orders once it’s in place[xxiii], but it requires foresight to set up. So, check with your contracting office if there are existing IDIQs or blanket contracts you can tap into right now for your needs. If yes, it can be one of the fastest ways to get a contractor on board for your project.

Pros:

- Quick Orders: If your lab already has access to an IDIQ contract that covers prototyping or engineering services, you can get work started quickly by issuing a task order. The big benefit is speed and less paperwork per order – terms and pricing are pre-set, so each new task is essentially a short statement of work and a one-step award[xxii].

- Flexible and Ongoing: IDIQs are great for ongoing or unpredictable needs. You don’t have to predict exactly what you’ll need up front; you establish a flexible contract and then order what you need when you need it. This is useful for a lab that expects to do many prototypes or experiments over time.

- Competition Done Upfront (or limited): If it’s a single-award IDIQ (only one vendor won it), then every task order is essentially sole-source to that vendor, which is very convenient (no further competition). If it’s a multiple-award IDIQ, you have a few chosen vendors and you can have a quick mini-competition among them for each task – still much quicker than a full open bid. Either way, the heavy competition happened when establishing the IDIQ, so day-to-day orders are streamlined.

Cons:

- Setup Time: Establishing a new IDIQ contract is not fast. It often requires a full solicitation, proposal reviews, and an award process. This could take months. So if you don’t have one in place, it’s not a quick fix for an immediate need.

- Planning Needed: IDIQs make sense if you foresee a recurring need or long-term program of prototyping or services. They are probably overkill if you just have a one-time quick project. They shine in long run, not always for a single rapid hire (unless you can piggyback on someone else’s IDIQ).

- Access to Existing IDIQs: Sometimes, as a researcher, you might not be aware of all the contract vehicles available. There may be agency-wide or DoD-wide IDIQ contracts your lab can use (for example, an engineering support IDIQ that multiple labs can order from). The challenge is knowing about them and getting access. You’ll need to work with contracting to see if an existing vehicle can be leveraged. If none exist, setting one up just for your prototype might not meet your immediate timeline.

SBIR/STTR Programs (Small Business Innovation Research/Technology Transfer)

What It Is

SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) and STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) are government programs that fund small businesses to do R&D and prototyping work. Agencies (including DoD) release topics, and small companies propose solutions. If selected, the company gets a Phase I (small grant/contract to prove concept, usually ~$50K–$250K) and potentially a Phase II (larger award to develop a prototype, usually ~$750K–$1.5M[xvi]). These are competitive awards intended to spur innovation. For a lab researcher, SBIR/STTR is a way to get R&D done by an external small business with government funding. However, it’s not a quick procurement tool – it’s more of a program to tap into for longer-term projects.

When to Use It

Consider SBIR/STTR for early-stage research ideas or if you can align your needs with the program’s timelines. If your project is not extremely time-sensitive and could benefit from extra funding, you might coordinate with your agency’s SBIR program office to issue a topic that fits your need. For example, if you have a year or more and want to explore a novel sensor technology, proposing an SBIR topic or encouraging a small business to apply could work. As a lab researcher, your role might be to mentor or partner with the small business (especially in STTR, which requires a nonprofit research partner). Important: SBIR isn’t a quick contracting fix for an urgent requirement; it’s more of a strategic tool to develop tech with small businesses. If you’re already working with a small company that has SBIR funding, leverage that relationship. And remember the payoff: if the company’s tech proves out in SBIR Phase II, you can then push for a Phase III contract awarded directly to that company (this is where you skip the normal competition, citing the SBIR success as justification)[xviii]. In summary, use SBIR/STTR when you have a bit more time and want to foster innovation for future capabilities – it’s a great program, but not your go-to for “needed it yesterday” projects.

Pros:

- Non-Dilutive Funding: SBIR/STTR awards provide funding to the small business to do the work, which means you are essentially contracting R&D without needing a big chunk of your own program’s budget. The money is dedicated to innovation.

- Small Business Focus: It’s a great way to engage small businesses and startups in solving DoD problems. These programs are specifically designed to give innovators a chance.

- Follow-On Sole Source: Here’s a big benefit – if a company successfully completes an SBIR project (Phase I or II), *the government can award follow-on contracts to them without competition. A successful SBIR project basically gives a sole-source justification for a Phase III (production or larger contract)[xvii]. This means if a lab likes the prototype from SBIR, it can continue working with that company more easily. (Phase III contracts can be much larger and directly awarded).

Cons:

- Slow to Start: SBIR/STTR is not fast. The process involves agencies posting topics, companies writing proposals, panels reviewing them, and then phased awards. This can take many months from topic idea to actual contract. It’s not ideal if you need an immediate prototype.

- Competitive and Uncertain: There’s no guarantee the company you want will win an SBIR, since it’s a competition. Also you have to align your project with an SBIR solicitation cycle or convince your agency to issue a topic – both can be challenging on a tight timeline.

- Structured Phases: The funding comes in phases with set amounts, which might be less flexible than a direct contract. You might get a feasibility study in Phase I, but it might take another proposal and award (Phase II) to get the full prototype built, adding time.

Which Federal Contracting Method is Right For You?

By understanding these federal contracting methods – OTA, SAP, micro-purchases, SBIR/STTR, GSA Schedules, and IDIQs – you as a lab researcher are better equipped to get external help on board rapidly. Each method has its niche, but all share a common goal: get innovative work started with minimal delay and red tape. Identify which route fits your scenario, then work hand-in-hand with your contracting office to make it happen. With a bit of preparation and the right approach, you can go from an idea to a contracted prototype partner in a surprisingly short time, allowing you to focus on the science and engineering rather than the paperwork. Good luck, and happy prototyping!

Schedule Your Free Consultation

Still not sure which federal contracting methods fit your project?

Consult with one of our expert engineers to discuss your project, answer some questions, and see if we can help. No commitment necessary – let’s talk shop!